4. Communication Between Neurons

The electrical changes taking place within a neuron, as described in the previous section, are similar to a light switch being turned on. A stimulus starts the depolarization (hand on switch), but the action potential runs on its own once a threshold has been reached (electricity moving through the wires to the light). The question is now, “What flips the light switch on?” Temporary changes to a neuron’s cell membrane voltage can result from stimuli in the environment, or from the action of one neuron on another. These temporary changes in membrane potential influence a neuron and determine whether an action potential will occur or not.

Synapses

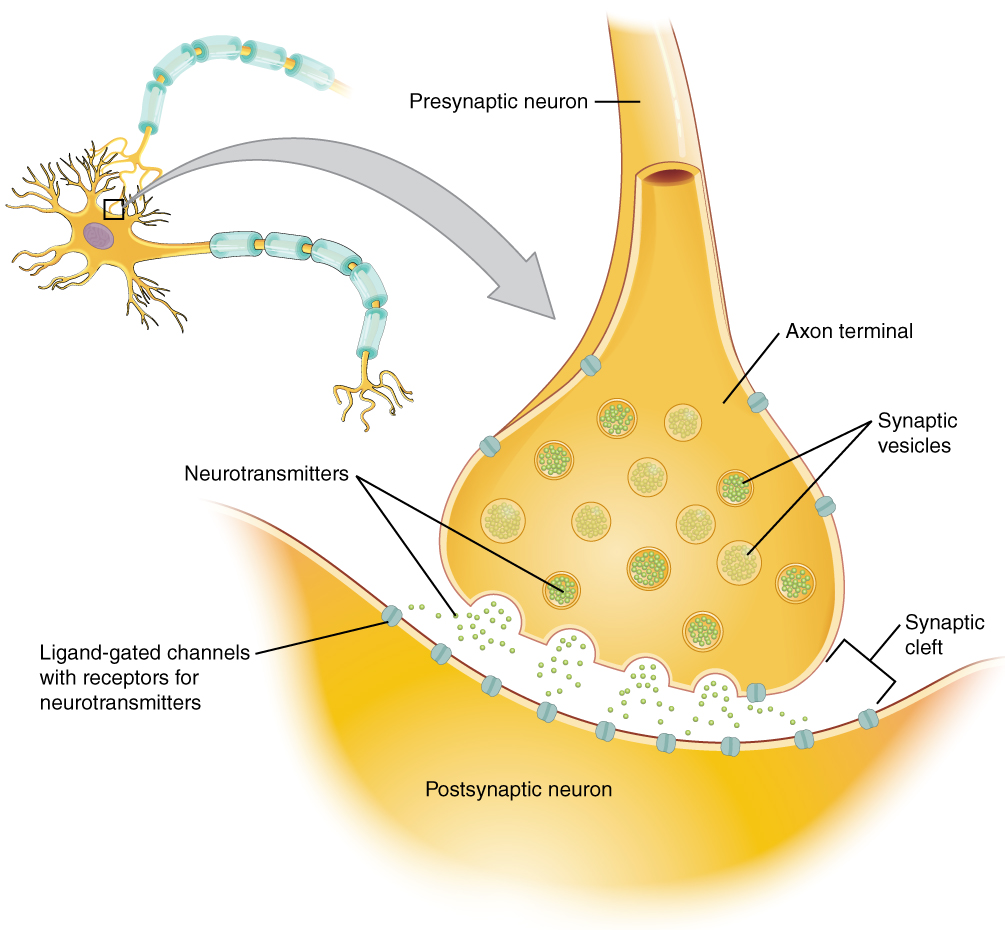

A synapse is the site of communication between a neuron and another cell. There are two types of synapses: chemical synapses and electrical synapses. In a chemical synapse, a chemical signal— a neurotransmitter—is released from the neuron and it binds to a receptor on the other cell. In an electrical synapse, the membranes of two cells directly connect through a gap junction so that ions can pass directly from one cell to the next, transmitting a signal. Both types of synapses occur in the nervous system, though chemical synapses are more common.

An example of a chemical synapse is the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) described in the chapter on muscle tissue. In the nervous system, there are many additional synapses that utilize the same mechanisms as the NMJ. All chemical synapses have common characteristics, which can be summarized in Table 12.1:

| Example Chemical Synapse (Table 12.1) | |

|---|---|

| Common Chemical Synapse Element | Specific element in a Skeletal Muscle Neuromuscular Junction |

| presynaptic element | somatic motor neuron axon terminal |

| neurotransmitter (packaged in vesicles) | acetylcholine |

| synaptic cleft | space between somatic motor neuron and muscle cell membrane |

| receptor proteins | nicotinic acetylcholine (cholinergic) receptor |

| postsynaptic element | postsynaptic element is the motor end plate of the sarcolemma |

| neurotransmitter elimination or re-uptake | degrading enzyme: acetylcholinesterase |

Neurotransmitter Release

When an action potential reaches the axon terminals, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the membrane of the synaptic end bulb open. Ca2+ diffuses down its concentration gradient and enters into the presynaptic neuron axon terminal (end bulb). Once Ca2+ is inside the presynaptic end bulb, it associates with proteins to trigger the exocytosis of neurotransmitter vesicles. The released neurotransmitter moves into the small gap between the cells, the synaptic cleft.

Once in the synaptic cleft, the neurotransmitter diffuses the short distance to the postsynaptic membrane and can bind to neurotransmitter receptors. Receptors are specific for the neurotransmitter, and the two fit together like a lock and key, and so a neurotransmitter will not bind to receptors for other neurotransmitters (Figure 4.1).

Neurotransmitter and Receptor Systems

Neurotransmitters vary greatly throughout the body, but one principle applies to all: neurotransmitters must bind to their own specific receptor, of which there can be subtypes. We will use acetylcholine (neurotransmitter) and its receptor (cholinergic) as an example. There are two subtypes of cholinergic receptors both of which bind acetylecholine: nicotinic receptors and muscarinic receptors (their names are based on the other chemicals that can also bind to the receptor). Nicotine will bind to the nicotinic receptor and activate it, just like acetylcholine. Muscarine, a product of certain mushrooms, will bind to the muscarinic receptor, just like acetylcholine. However, nicotine will not bind to the muscarinic receptor and muscarine will not bind to the nicotinic receptor. Skeletal muscle NMJs always involve nicotinic cholinergic receptors and when acteylcholine binds to nicotinic receptors, a Na+ ligand gated channel opens. Muscarinic receptors are found sometimes with with K+ ligand gated channels and other times with Na+ ligand gated channels, differing throughout the body. For example, when acetylcholine binds to a muscarinic receptor on the pace-maker cells of the heart, K+ ligand gated channels open and heart rate slows down. When acetylcholine binds to a muscarinic receptor on the small intestine muscle, a Na+ ligand gated channel opens and the muscle activates (contracts). This variability in receptor/channel combinations is common throughout the body and occurs for many other neurotransmitters like epinephrine (adrenaline), serotonin and dopamine.

Neurotransmitters are classified in many ways based on their structural chemical make up or their functional common effects. Chemically, neurotransmitters can be small, amino acid based molecules, released from neurons as amino acids themselves (ie: glutamate, glycine) or as enzymatically modified relatively simple molecules (acetylecholine, ATP or biogenic amines such as dopamine). Larger molecule neurotransmitters are more complex proteins (3-36 amino acids long) called neuropeptides. There are more than 100 different peptides and include those such as enkephalins or endorphins, each with their own receptor types and subtypes that bind them.

Types of Neurotransmitters

Small Molecule Neurotransmitters: Amino Acids, Acetylcholine, and Purine Neurotransmitters

Amino Acids: Glutamate (Glu), GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid, a derivative of glutamate), and glycine (Gly) are common amino acid neurotransmitters. These amino acids have an amino group and a carboxyl group in their chemical structures. Glutamate is one of the 20 amino acids that are used to make proteins. Each amino acid neurotransmitter would be part of its own system, namely the glutamatergic, GABAergic, and glycinergic systems. They each have their own receptors and do not interact with each other. Amino acid neurotransmitters are eliminated from the synapse by reuptake in the neuron that released them. A pump in the presynaptic cell membrane, or sometimes a neighboring glial cell, removes the amino acid from the synaptic cleft so that it can be recycled, repackaged in vesicles, and released again.

The amino acid neurotransmitters, glutamate, glycine, and GABA, are almost exclusively associated with just one effect. Glutamate is often considered an excitatory amino acid, but only because glutamate receptors in the adult cause depolarization of the postsynaptic cell (by changing membrane permeability to Na+ or Ca2+). Glycine and GABA are considered inhibitory amino acids, because their receptors typically cause hyperpolarization (by chaniging membrane permability to Cl– or K+).

Acetylcholine and ATP: Acetylcholine was described above, including its excitatory or inhibitor effects when binding to various cholinergic receptors. ATP, the energy molecule and a purine chemically, has been found to act as a neurotransmitter in both the peripheral and central nervous system, often associated with excitatory effects.

Small Molecule Neurotransmitters: Biogenic Amines

Biogenic amines are a group of neurotransmitters that are enzymatically made from amino acids. They have amino groups in them, but no longer have carboxyl groups and are therefore no longer classified as amino acids. Members of this group include serotonin, histamine and the catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine/noradrenaline and epinephrine/adrenaline). Serotonin (which is the basis of the serotonergic system) is made from tryptophan and has its own specific receptors. Dopamine is part of its own system, the dopaminergic system, which has dopamine receptors. Norepinephrine and epinephrine belong to the adrenergic neurotransmitter system. The two molecules are very similar and bind to the same receptors, which are referred to as alpha and beta receptors. The chemical epinephrine (epi- = “on”; “-nephrine” = kidney) is also known as adrenaline (renal = “kidney”), and norepinephrine is sometimes referred to as noradrenaline. The adrenal gland produces epinephrine and norepinephrine to be released into the blood stream as hormones. Once released into the synatpic cleft, all of these neurotransmitters are transported back into their respective presynaptic end bulb for repackaging and re-release.

The biogenic amines have mixed effects. For example, the dopamine receptors that are classified as D1 receptors are excitatory whereas D2-type receptors are inhibitory. Biogenic amine receptors can have even more complex effects because some may not directly affect the membrane potential, but rather have an effect on gene transcription or other metabolic processes in the neuron. The characteristics of the various neurotransmitter systems presented in this section are organized in Table 12.2.

Large Molecule Neurotransmitters: Neuropeptides

A neuropeptide is a neurotransmitter molecule made up of chains of amino acids connected by peptide bonds; essentially a mini-protein. Neuropeptides are often released at synapses in combination with another neurotransmitter, and they often act as hormones in other systems of the body, such as oxytocin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) or substance P. In addition, sometimes neuropeptides contain other neuropeptides within them! In the case of endorphins, once released, endorphins are cleaved by extracellular enzymes to produce enkephalins, both of which bind to opiod receptors to modulate pain perception in the brain.

The characteristics of the various neurotransmitter systems presented in this section are organized in Table 12.2.

| Characteristics of Neurotransmitter Systems (Table 12.2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System | Cholinergic | Amino acids | Biogenic amines | Neuropeptides |

| Neurotransmitters | Acetylcholine | Glutamate, glycine, GABA | Serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, norepinephrine, (epinephrine) | Met-enkephalin, beta-endorphin, VIP, Substance P, etc. |

| Receptors | Nicotinic and muscarinic receptors | Glu receptors, gly receptors, GABA receptors | 5-HT receptors, D1 and D2 receptors, α-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptors | Receptors are too numerous to list, but are specific to the peptides. |

| Elimination | Degradation by acetylcholinesterase | Reuptake by neurons or glia | Reuptake by neurons | Degradation by enzymes called peptidases |

| Postsynaptic effect | Nicotinic receptor causes depolarization. Muscarinic receptors can cause both depolarization or hyperpolarization depending on the subtype. | Glu receptors cause depolarization. Gly and GABA receptors cause hyperpolarization. | Depolarization or hyperpolarization depends on the specific receptor. For example, D1 receptors cause depolarization and D2 receptors cause hyperpolarization. | Depolarization or hyperpolarization depends on the specific receptor. |

Receptor Mechanism of Action

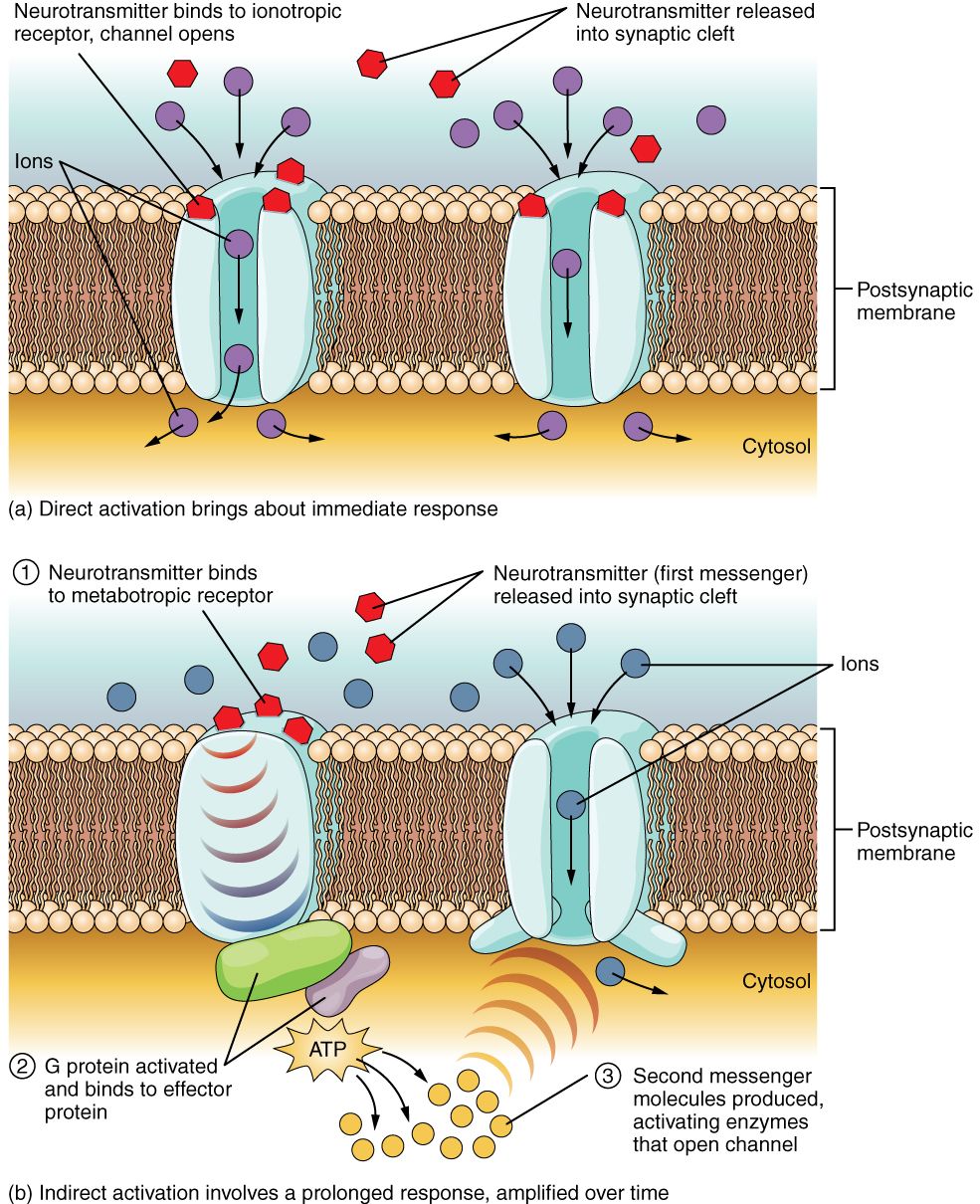

The important thing to remember about neurotransmitters, and signaling chemicals in general, is that the effect is entirely dependent on the receptor. Neurotransmitters bind to one of two classes of receptors at the cell surface, ionotropic or metabotropic (Figure 4.2). Ionotropic receptors are ligand-gated ion channels, such as the nicotinic receptor for acetylcholine or the glycine receptor. A metabotropic receptor involves a complex of proteins that result in metabolic changes within the cell. The receptor complex includes the transmembrane receptor protein, a G protein, and an effector protein. The neurotransmitter, referred to as the first messenger, binds to the receptor protein on the extracellular surface of the cell, and the intracellular side of the protein initiates activity of the G protein. The G protein is a guanosine triphosphate (GTP) hydrolase that physically moves from the receptor protein to the effector protein to activate the latter. An effector protein is an enzyme that catalyzes the generation of a new molecule, which acts as the intracellular mediator, or the second messenger.

Different receptors use different second messengers. Two common examples of second messengers are cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and inositol triphosphate (IP3). The enzyme adenylate cyclase (an example of an effector protein) makes cAMP, and phospholipase C is the enzyme that makes IP3. Second messengers, after they are produced by the effector protein, cause metabolic changes within the cell. These changes are most likely the activation of other enzymes in the cell. In neurons, they often modify ion channels, either opening or closing them. These enzymes can also cause changes in the cell, such as the activation of genes in the nucleus, and therefore the increased synthesis of proteins. In neurons, these kinds of changes are often the basis of stronger connections between cells at the synapse and may be the basis of learning and memory.

Graded Potentials

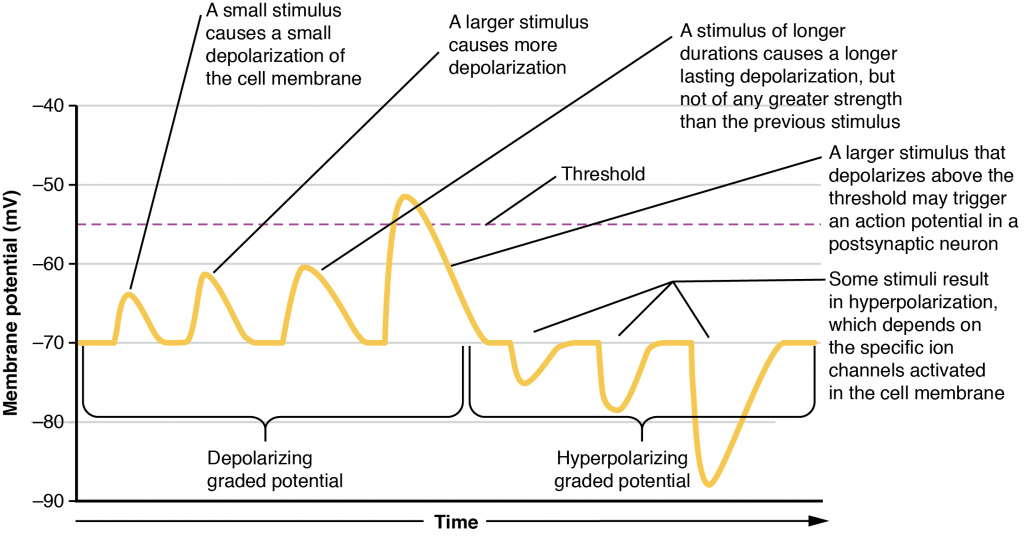

Local changes in the membrane potential away from resting levels are called graded potentials and are usually associated with opening gated channels on the membrane a neuron. The type and amount of change in the membrane potential is determined by the ion that crosses the membrane, how many ions cross and for how long. Graded potentials can be of two sorts, either they are depolarizing (above resting membrane potential) or hyperpolarizing (below resting membrane potential) (Figure 4.3). Depolarizing graded potentials are often the result of Na+ or Ca2+ entering the cell. Both of these ions have higher concentrations outside the cell than inside; because they have a positive charge, when they move into the cell the membrane becomes less negative inside relative to the outside. Hyperpolarizing graded potentials can be caused by K+ leaving the cell or Cl– entering the cell. The membrane becomes more negative if a positive charge moves out of a cell or if a negative charge enters the cell. Graded potentials are transient and are dissipated as they move away from the site of the initial stimulus.

When ion channels are left open longer or more channels are opened (for the same ion), the stimulus affecting a neuron is bigger. A “bigger stimulus” occurs due to a more painful stimulus, a heavier load, a brighter light etc. These larger stimuli induce larger graded potentials of longer duration in neurons and can be either depolarizing or hyperpolarizing.

For the unipolar cells of sensory neurons—both those with free nerve endings and those within encapsulations—graded potentials develop in the dendrites and influence the generation of an action potential in the axon of the same cell. This is called a generator potential. For other sensory receptor cells which are not neurons, such as taste cells or photoreceptors of the retina, graded potentials in receptor cell membranes result in the release of neurotransmitters at synapses with sensory neurons. This is called a receptor potential, and we will consider this type of graded potential during a discussion of the special senses.

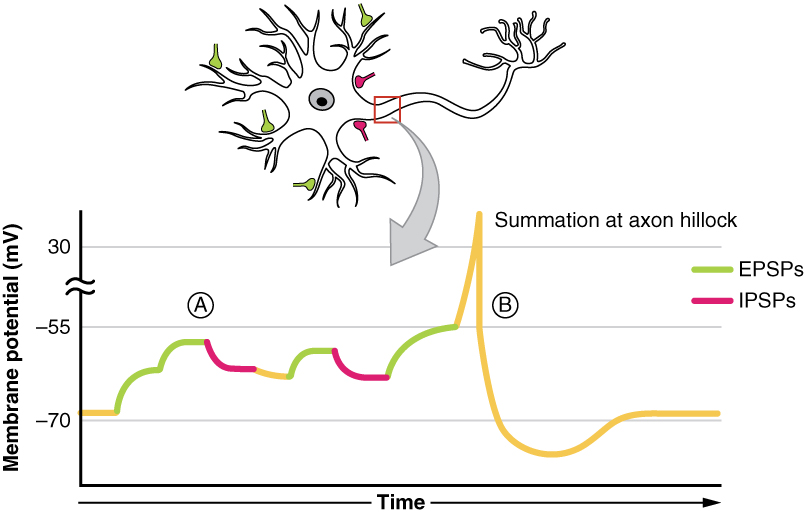

A postsynaptic potential (PSP) is the graded potential in the dendrites or cell body of a neuron that is receiving synapses from other cells. Postsynaptic potentials can be depolarizing or hyperpolarizing. Depolarization in a postsynaptic potential is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move toward threshold. Hyperpolarization in a postsynaptic potential is an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move away from threshold.

Summation

All types of graded potentials will result in small changes (either depolarization or hyperpolarization) in the voltage of a membrane. These changes can lead to the neuron reaching threshold if the changes add together, or summate. The combined effects of different types of graded potentials are illustrated in Figure 4.4. If the total change in voltage that reaches the initial segment (or trigger zone) is a positive 15 mV, meaning that the membrane depolarizes from -70 mV (resting membrane potential) to -55 mV (threshold), then the graded potentials will result in the initiation of an action potential.

Graded potentials summate at a specific location at the beginning of the axon to initiate the action potential, namely the initial segment. For sensory neurons, the initial segment is directly adjacent to the dendritic endings (since the cell body is located more proximally). For all other neurons, the initial segment of the axon is found at the axon hillock and it is where summation takes place. These locations have a high density of voltage-gated Na+ channels that initiate the depolarizing phase of the action potential and is often referred as the trigger zone.

Summation can be spatial or temporal, meaning it can be the result of multiple graded potentials occurring simultaneously at different locations on the neuron (spatial), or all at the same place but in rapid succession (temporal). Spatial and temporal summation can act together, as well. Since graded potentials dissipated with distance and time, summation is the total change in voltage due to all spatial and temporal graded potentials that reach the trigger zone or initial segment at each moment.

Disorders of the Nervous System

The underlying cause of some neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, appears to be related to proteins—specifically, to proteins behaving badly. One of the strongest theories of what causes Alzheimer’s disease is based on the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, dense conglomerations of a protein that is not functioning correctly. Parkinson’s disease is linked to an increase in a protein known as alpha-synuclein that is toxic to the cells of the substantia nigra nucleus in the midbrain.

For proteins to function correctly, they are dependent on their three-dimensional shape. The linear sequence of amino acids folds into a three-dimensional shape that is based on the interactions between and among those amino acids. When the folding is disturbed, and proteins take on a different shape, they stop functioning correctly. But the disease is not necessarily the result of functional loss of these proteins; rather, these altered proteins start to accumulate and may become toxic. For example, in Alzheimer’s, the hallmark of the disease is the accumulation of these amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex. The term coined to describe this sort of disease is “proteopathy” and it includes other diseases. Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, the human variant of the prion disease known as mad cow disease in the bovine, also involves the accumulation of amyloid plaques, similar to Alzheimer’s. Diseases of other organ systems can fall into this group as well, such as cystic fibrosis or type 2 diabetes. Recognizing the relationship between these diseases has suggested new therapeutic possibilities. Interfering with the accumulation of the proteins, and possibly as early as their original production within the cell, may unlock new ways to alleviate these devastating diseases.